Category one, gunshot wound to abdomen. In minutes, the trauma team at Temple University Hospital has evaluated the bloodied young man wheeled into their trauma bay and decided to take him to the operating room for life-saving surgery. Now, Jessica Beard’s hands move deftly inside the large incision on the patient’s abdomen checking for damage to the major blood vessels, kidneys, liver, and spleen. Finding them unscathed, she turns her attention to a bullet-damaged part of the intestine, reconstructing it with a quick combination of staples and stitches.

As Beard discards her bloodied gloves and her young patient begins to wake up from anesthesia, she allows herself a brief moment of relief. This young man—who should be too young to know the brutalization of a gun—will live, and soon be reunited with his mother, who has been pacing the waiting room with silent tears running down her cheeks.

Thirty minutes later, Beard’s phone pings twice in her pocket in rapid succession. Category one, gunshot wound to chest, reads one alert. Category one gunshot wound to leg, patient 2, reads the other. Beard and her team launch into their fine-tuned choreography again, determined to save these lives too.

This is a snapshot of one trauma surgeon’s experience but this scene is playing out every day across the country.

Gun violence has become an unavoidable reality of American society. The barrage of news reports about shootings comes in such quick succession now that we no longer have time to catch our breath before a new tragedy takes hold of the public’s attention. Almost every day this year, a new American community has grieved in the wake of a loaded gun.

Yet this reality is one that is unique to the United States, at least among developed countries. The U.S. has more gun-related deaths than any other developed country in the world. In 2020, a total of 45,222 people died in the U.S. from gun-related injuries. In 2018, it was estimated that Americans own a total of 393 million guns, meaning that the U.S. also has the highest number of guns per capita in the world.

It’s easy to see a correlation between these figures, but what’s harder to understand is why something hasn’t been done to address the problem. After every shooting that captures national attention, grieving family members and citizens ask the same questions: Why does the U.S. have a gun problem? How can we improve gun laws and policies? And how can we stop shootings from happening in the future?

Temple University experts, like Jessica Beard and many others, have been working tirelessly to research this issue and equip their students with the tools they need to also become part of the solution to America’s gun epidemic.

So, we asked these experts to paint a picture of the evolution of American gun culture and the ways we can solve this gun epidemic so that, one day, surgeons like Beard can stop witnessing an endless, gory stream of young people being mutilated or killed by guns.

Key takeaways

- Mark Rahdert, professor of constitutional law: When the Second Amendment was reinterpreted by the Supreme Court in 2008, it ruled that U.S. citizens have a constitutional right to carry firearms for self-defense. This was a stark departure from past interpretations of the amendment that understood its meaning in relation to the development of state government-organized militias.

- Timothy Welbeck, assistant professor of Africology and African American studies and director of Temple University’s Center for Anti-Racism: The Black Panthers interpreted the Second Amendment to mean private citizens could bear arms. They used this interpretation to legally provide armed defense against police brutality in their communities. This approach initially met significant backlash until the gun lobby adopted and distorted it with public campaigns that culminated in the Supreme Court adopting their interpretation in 2008.

- Laurence Steinberg, professor of psychology and neuroscience: During adolescence, as a consequence of normal brain development, there is often a gap between the strength of our impulses and our ability to control them. This is, in part, why we see a high percentage of adolescents perpetrating gun violence.

- Jennifer Pollitt, assistant director of the Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Department: Men perpetrate a majority of all gun violence and this may be due to the fact that, as boys, they are more likely to be socialized to feel entitled to their anger and taught to solve problems with violence.

- Caterina Roman, professor of criminal justice: A lack of access to social services and the presence of open air drug markets selling illegal drugs—particularly fentanyl—are two factors that are leading to gun violence in the U.S. Both factors were exacerbated by the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

- Michael Sances, associate professor of political science: Although the majority of Americans support some form of gun reform, the disproportionate political power of rural areas has made it difficult to pass legislation.

- Jessica Beard, trauma surgeon, public health researcher at Temple University Hospital and director of research for the Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting: The Dickey Amendment, which was enacted in 1996 but is no longer in effect, greatly limited the country’s ability to collect data that public health professionals need to better understand the complexities of this issue and develop effective solutions to address it.

What does the Constitution actually say about gun ownership?

The Second Amendment is at the heart of the conversation about American gun ownership. Yet the language of the amendment has been the source of debate for decades. So what does the Constitution actually say about gun ownership and what does it mean?

The exact wording of the Second Amendment reads: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Mark Rahdert, professor of constitutional law, explains that there are two ways to interpret the Second Amendment. Some focus simply on the second half of the sentence which implies that American citizens have the right to own firearms. Others, who look at the sentence in its entirety, argue that the Second Amendment refers to a citizen’s ability to form and maintain state-level militias in order to defend themselves if needed.

According to Rahdert, Article I of the Constitution gave Congress the authority to create a standing, central army and navy. But opponents to this article were afraid that the existence of a central army would destroy the ability of individual states to protect themselves because they wouldn’t be able to muster their own forces when needed.

In response, the Second Amendment was created to ensure that the states could continue to have their own state militias. “And at the time the document was drafted, the traditional way to supply militias was to have each individual member of the militia provide their own firearms,” says Rahdert.

This understanding, that the Second Amendment referred to a citizen’s right to own a firearm for the sole purpose of forming a militia, was supported by the Supreme Court for well over a century of American history until 2008.

In 2008, the District of Columbia v. Heller Supreme Court decision ruled that the Second Amendment should be interpreted as though it consisted of only the second half of the sentence. The court then used selective tidbits of American history to maintain that U.S. citizens now had a constitutional right to carry and use firearms for the purpose of self-defense.

Although he disagrees with the court’s 2008 interpretation of the amendment, Rahdert explains that it was an attempt by the Supreme Court to strike a blow against the idea that the Constitution’s meaning evolves over time as our society evolves. Instead, it was a step towards confirming the idea that the Constitution’s meaning was fixed the moment it was ratified, and does not change or evolve over time even as circumstances in our society change.

This 2008 Supreme Court decision set the stage for America’s ongoing battle over gun reform.

The birth of American gun culture

Regardless of how the Second Amendment is interpreted, our society’s fixation on it is a relatively new phenomenon.

“Prior generations of Americans thought about the Second Amendment in the way people today think about the Third Amendment. And by that, I mean they just didn’t think about it,” says Timothy Welbeck, assistant professor of Africology and African American studies and director of Temple University’s Center for Anti-Racism.

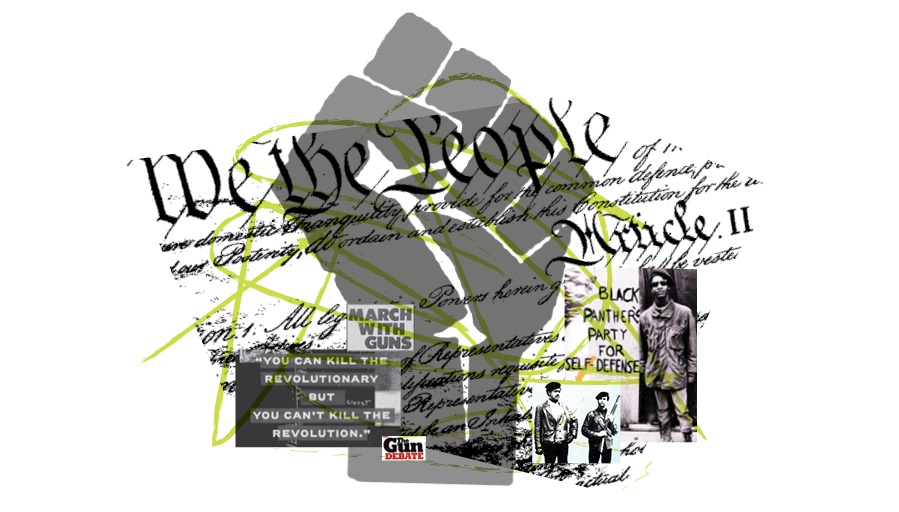

The birth of our current interpretation of the Second Amendment started in the 1960s from the Black Panther Party for Self-defense. At the time, Huey Newton was a law student looking for a solution to what he considered to be state-sanctioned violence against the Black community. He found his solution within the ambiguity of the Second Amendment.

Eventually, this language was included in the Black Panther Ten-point Program: “The Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States gives a right to bear arms. We therefore believe that all Black people should arm themselves for self-defense.” In this moment, our country’s relationship to guns began to change.

Welbeck points out that our country’s long relationship to guns is paradoxical. Owning guns first became common practice for American slave owners as a brutally efficient way to control their enslaved populations.

Fast-forward to the 1960s when the Black Panthers reinterpreted the Second Amendment as a way to protect themselves against police brutality. When news started to spread that members of Black Panthers were roaming the streets of California with firearms, California quickly passed legislation to restrict gun ownership in the state via the Mulford Act.

Armed with the Black Panthers’ new interpretation of the Second Amendment, Welbeck explains that “the NRA then began to adopt a more aggressive approach, eroding restrictions on guns while also reshaping the public discourse around what the Second Amendment says about gun ownership.” The conversation quickly reoriented itself back to one about white people needing guns in order to control the Black community or fight a tyrannical government.

“That fear became baked into the propaganda for gun ownership that we still hear in a coded way today: ‘You need a gun because what happens if a scary Black person comes at you and you can’t defend yourself?’” says Welbeck. What’s notable about this shift is that, before the 1960s, the National Rifle Association was largely devoted to promoting gun safety, and was seen as an outdoor recreation-focused organization that celebrated marksmanship.

Understanding modern American gun violence

So there was a dramatic shift in the 1960s that changed the way we thought about our relationship with guns. Then the 2008 Supreme Court decision locked in a new interpretation of the Second Amendment that gave everyone the freedom to carry a firearm.

From there, a lack of social services and the presence of active drug markets selling easy-to-obtain illegal substances such as fentanyl, combined with the COVID-19 pandemic, exacerbated America’s gun problem to the record-breaking levels we see today.

Professor of Criminal Justice Caterina Roman points out that many Americans found it harder to access social services like health and mental healthcare, public transportation, and recreational services to keep youth busy during the pandemic. Communities with high rates of crime were hit especially hard by that lack of access to social services, because victims of crime-related trauma need adequate services to help them recover and youth benefit from keeping active and being involved in pro-social activities.

When those services fail to exist and social networks are weakened, Roman says stress and anxiety are likely to increase, and residents might not feel protected. Youth and young adults may be more likely to carry and use guns in order to “stop disputes on their own.”

Roman says that illegal drugs have historically been linked with increases in gun violence as well. Previous peaks in gun homicides coincide with the rise of opioids in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and the height of the crack/cocaine epidemic in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

According to Roman, her research in Philadelphia shows that the COVID-19 pandemic may have led to another spike in illegal drug use, and in turn a major disruption in drug markets. People knew they could make money selling fentanyl, so out of desperation caused by the pandemic, they entered the brutal and competitive market of selling this illegal drug.

Roman’s research suggests that more people trying to sell these drugs meant more competition, more competition meant more interpersonal disputes, and more interpersonal disputes meant more people were going out and buying guns. Roman says this is how gun violence increased in neighborhoods where drugs are sold.

This dynamic is likely contagious, according to Roman. The increasing violence around the illegal drug market then leaks out to the rest of the community. Community members feel more motivated to acquire guns, especially when there is a small likelihood of facing legal consequences. This, in turn, leads to crime contagion, a phenomenon where people are more likely to commit crime because crime is already being committed around them without repercussions.

The connection between brain development and violent impulses

The devastation caused by COVID-19 helps us better understand why the levels of American gun violence have become so extreme. But it doesn’t explain why we are the only developed country with such high rates of gun violence, when the rest of the world was equally impacted by the pandemic.

Laurence Steinberg, professor of psychology and neuroscience, has dedicated much of his career to understanding why young people—especially young Americans—are so much more likely to engage in violence and other types of reckless behavior than people of any other age group.

“We know from FBI data that the peak age for violent crime in the U.S. is around 19 or 20 and that has stayed pretty constant over the years. So this seems to be a period of development when there is greater risk for people to commit violent acts,” says Steinberg. As someone who specializes in adolescent brain and behavioral development, this is a critical data point to him.

The scientific community has known for some time that the brain does not finish maturing until the mid-twenties. But through his extensive research on development between ages 10 and 30, Steinberg was able to pinpoint a temporary developmental gap between impulsivity and self-control during adolescence. He believes that it’s in this gap where we can find the neurobiological contributors to some of America’s gun violence problems.

This period of still-developing self-control and easily aroused impulses has an unfortunate overlap with increased social sensitivity. “The activation of what is sometimes called the ‘social brain’ makes young people very attentive to the opinions of their peers and makes them very sensitive to feeling that they’re unpopular or disliked,” says Steinberg.

In addition, his research also found the impulse control gap is greatest during late adolescence and wider among males than among females. This is likely due, in part, to the impact of testosterone, which has been connected to aggressive behavior in mammals. During puberty, there is a higher increase in testosterone in males than in females.

But Steinberg cautions against jumping to the common conclusion that young men will unavoidably be violent as a fact of nature. “Testosterone may explain why males are more likely to have these aggressive impulses than females. But we know that the vast majority of young men don’t act on their most violent impulses. There might be a gap in impulse control but most young people at this age still have the capacity to know right from wrong, and most are able to exert self-control when they need to,” says Steinberg.

Steinberg studied this gap in 11 different countries across Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas, and found it occurred in virtually all of them. And in the countries he has studied, there is also a peak in risky behavior during late adolescence.

Yet only American adolescents and young adults are likely to commit violent acts with firearms to the extent that they do. Steinberg believes this is due to how easy it is for young people to obtain firearms in the U.S. And, in his mind, this is why American teens with easy access to firearms have had such a lethal impact on American communities.

Convicted mass shooter Evan Ramsey unknowingly echoed Steinberg’s point in a 2018 interview with 60 Minutes. “I got tired of being picked on and I decided to take the shotgun to school,” Ramsey said during the interview. “If I didn’t have access to a gun, I wouldn’t be doing the prison sentence that I’m doing now.” Ramsey, who is serving a 198-year sentence, was 16 years old when he brought a shotgun to his school in Bethel, AK, and killed two and injured two others. The shotgun he used was stored in an unlocked gun rack in his home.

Why men perpetrate almost all gun violence

According to The Violence Project, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research center dedicated to violence prevention and intervention in America, 47 of the 147 instances of gun violence they studied were perpetrated by young men between the ages of 11–24. But when age is taken out of the equation, a startling picture emerges: 143 of the 147 instances of gun violence were perpetrated by men. In other words, almost all instances of gun violence they studied were perpetrated by men.

The United Nation’s Office on Drugs and Crime similarly found that about 90% of the world’s homicides were perpetrated by men and that, in 2017, half of all homicides were committed with a firearm.

Steinberg’s research helps provide clarity about why young men commit violence with firearms, but a deeper understanding of American men of all ages is needed to understand the broader pattern of why men are almost always the perpetrators of this violence.

Jennifer Pollitt, assistant director of the Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Department, starts her Men and Masculinities course with the same bell hooks quote each year: “The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves.” To Pollitt, this quote explains so much about the challenges facing American society and provides particular clarity about the startling relationship between gender and gun violence.

“American gun violence transcends race, transcends class, transcends ability, it transcends so much. But it doesn’t transcend gender. Gender is the number one factor that will predict who is more likely to use a gun to solve a problem,” says Pollitt.

The reason why men are so much more likely to engage in this kind of violent behavior comes down to socialization, according to Pollitt. Most boys are socialized to cut off all emotions that would associate them with being feminine including feelings of vulnerability and grief, and instead are encouraged to express anger and dominance.

Over the course of their childhoods, most American boys will be continuously exposed to this messaging from a variety of sources: from the kindergarten teacher who says boys shouldn’t play with dolls, to the grandfather who gives the advice to “show ‘em who’s boss” when addressing conflict with schoolmates, to the baseball coach that screams at his players to “stop throwing like girls,” to the father who gruffly passes on the instruction to “man up” in the face of tears.

Pollitt believes that Americans—as well as many other countries around the world—have constructed an entire gender identity based on what it is not instead of what it is. The end result? The emotional stunting of American men. And people who are not able to process and express their emotions are more likely to solve their problems through violence.

“Being a ‘man’ in America is often about who can instill fear more readily and who’s the toughest,” says Pollitt. And because a gun is the ultimate source of power, she believes this becomes a deadly—though obvious—recipe for men using guns to assert their power over others.

While Pollitt acknowledges that mental health issues factor into the high rates of gun violence in America, she explains that gun violence would be pervasive across gender if mental health was the primary cause. “America has plenty of girls and women who suffer with mental health issues, and yet they’re not picking up a gun and shooting someone,” says Pollitt.

Why is it so difficult to reduce gun violence in America?

When 20 elementary school children were murdered in 2012 by an assault weapon-wielding gunman, people across the country were certain that the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting would inspire meaningful reforms to gun legislation. The Assault Weapons Ban of 2013 was introduced in the aftermath of the attack which would have banned the sale, transfer or manufacture of certain assault-style weapons and high-capacity magazines.

But just weeks after the children were buried, the bill was defeated in the Senate by a vote of 60-40.

The Senate has historically been a barrier to passing popular legislation, and Professor of Political Science Michael Sances says that is because the Senate is not designed to represent the views of the majority of the country. With two Senators representing each state, the Senate gives equal political power to every state regardless of its population.

Additionally, for an issue to be voted on and bypass the Senate filibuster it needs to be supported by a supermajority of Senators. Sances says these features of the Senate give unequal weight to rural areas of the country and reduces the political power of urban areas affected by gun violence.

Americans broadly support certain gun reform measures, like preventing people with mental illness from purchasing a firearm. However, it only takes 40 Senators, who may represent the views of the minority of the country, to prevent these measures from being voted on.

Legislators aren’t the only group experiencing barriers to addressing gun violence. Healthcare professionals, criminologists and other researchers are increasingly treating gun violence as a public health issue in their approach to developing solutions.

A public health approach to any problem requires accurate monitoring and data collection. But collecting data on gun violence has become nearly impossible since the enactment of the Dickey Amendment in 1996, which stipulated that federal funding could not be used for research that would support legislation designed to limit the rights of gun owners.

As a result, the CDC was prevented from tracking and researching gun violence as a health problem from 1996 to about 2015, according to Jessica Beard, a public health researcher at Temple University Hospital and Director of Research for the Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting. And while there is reliable data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on fatal shootings, Beard explains that collection of data points related to nonfatal shootings has been greatly hampered by the Dickey Amendment.

“We have not been collecting data on gun violence because gun violence research was censored by our government,” Beard says. “In the 1990s research was coming out that said guns don’t make you safe and that you’re more likely to be killed with a gun if you have a gun.” She says this research angered the gun lobby, who pressed Congress to respond with a ban on federally funded gun violence prevention research.

This lack of comprehensive data has made it difficult for researchers like Beard and criminologists like Roman to address the gun violence crisis through a public health approach. “Because of the lack of government funding, the country has historically had very few researchers who are experts in firearm injury policy and prevention,” Beard says.

This may soon change, however. A 2018 interpretation of the Dickey Amendment paved the way for federal funding to be used to research gun violence, as long as the research does not specifically advocate for gun reform. $25 million was subsequently included in the 2020 federal budget for the CDC and National Institutes of Health to research gun violence and ways to prevent it.

Putting it all together

Understanding the full scope of the country’s relationship with guns and its history of gun violence is an important first step towards finding meaningful solutions. The more the problem is understood, the closer we can get to finally ending the gun violence epidemic. In the second part of this series, Understanding American gun violence part 2: How to solve the American gun epidemic, these Temple experts lay out a variety of solutions that can help the country make significant strides toward ending gun violence. Read on to see what they have to say.